At the same time, China has accelerated the largest and most comprehensive military modernization effort in history. The People’s Liberation Army has upgraded its strategic rocket forces and its space and cyber-capabilities. Beijing has married these advances with increasing assertiveness and coercive behavior across the region. Since 2017, it has sought to use economic tools to punish Australia for speaking out on the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic. It has also dialed up political and military pressure on Japan and other countries with whom it has disputes over territory and maritime claims in the East China and South China Seas, precipitated a low-grade border war with India in the Himalayas, increased military tensions in Taiwan, and essentially quashed Hong Kong’s remaining autonomy.

These developments alone should have been enough to bring Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington closer together. But then came Russia’s February invasion of Ukraine, just days after Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin announced a “no limits” partnership. Since then, China appears to be carefully calibrating its political support for Moscow so as not to trigger sanctions from the West. Nevertheless, the Russian-Chinese partnership poses a clear threat to the existing international order and the framework of international laws, rules, and norms that underpins it. As Kishida has repeatedly warned, “Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow.”

Closer collaboration would advance the foreign policy goals of Japan, South Korea, and the United States.

Closer collaboration would advance the foreign policy goals of all three counties. For Biden, the United States’ five treaty alliances with Australia, Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Thailand are at the heart of the government’s Indo-Pacific strategy. Militarily, Japan and South Korea are critical to deterring conflicts on the Korean Peninsula and in the Taiwan Strait; that deterrence is stronger when the allies speak as one and act together. As democracies and as the world’s third- and tenth-largest economies, Japan and South Korea are vital to advancing the Biden administration’s overarching goal for the region: “an Indo-Pacific that is free and open, connected, prosperous, secure, and resilient.”

In short, although the United States remains the most powerful actor in Asia, it needs the support of key partners such as Japan and South Korea to buttress the rules-based international order. From the beginning, the Biden administration has worked to rebuild the trilateralism that former U.S. President Donald Trump largely discounted. Trump was indifferent to the bickering between Seoul and Tokyo, reportedly deflecting requests to intervene by saying, “Why do I have to get involved in everything?”

For Yoon, improving trilateral relations with the United States and Japan would provide the strongest possible foundation for dealing with China. Seoul’s voice with Beijing is stronger in concert with Washington’s and Tokyo’s than it is solo. Moreover, the belief held by some South Koreans that there is no cost to bad relations with Tokyo is wrong. Two major new initiatives in East Asia—the Quad (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue) an alliance that unites Australia, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and Japan’s “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” strategy—moved forward without South Korea in no small part because of its poor relations with Japan. Joining together with Tokyo and Washington would not just bolster South Korea’s policies to deter North Korea but also serve Yoon’s aspiration for South Korea to play a pivotal role in everything from supply chains to development assistance—areas in which Seoul’s two allies are key players.

For Kishida, trilateral cooperation would be good for “realism diplomacy,” as he described his foreign policy approach in a speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue in June. No country in Asia has been more affected by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine than Japan, which for years under the late prime minister Shinzo Abe assiduously sought to build a cooperative relationship with Putin in a vain attempt to secure the return of the Northern Territories, four islands off Japan’s northernmost prefecture that Russia occupied in the waning days of World War II.

Japan faces a regional security environment more challenging than at any time since World War II.

Kishida’s bold response to the war in Ukraine—imposing sweeping financial sanctions and export controls on Moscow and offering robust assistance to Kyiv—effectively flipped the table on years of Japanese foreign policy. But Japan now faces a regional security environment more challenging than at any time since World War II. In his speech in June, Kishida called for “strengthening the rules-based free and open international order” and closer cooperation on economic issues, such as supply chain and infrastructure resilience. All these goals would benefit from trilateral cooperation and closer ties with South Korea.

READ ALSO: US: DARPA successfully tests hypersonic missile

Biden, Kishida, and Yoon deserve credit for being forward-leaning in their support of trilateralism. Even in the absence of clear deliverables, the mere fact that the meeting in Madrid took place sends a powerful message to the citizens and bureaucracies in Japan and South Korea that trilateral cooperation is a priority. But the meeting must be followed by action.

A PLAN OF ACTION

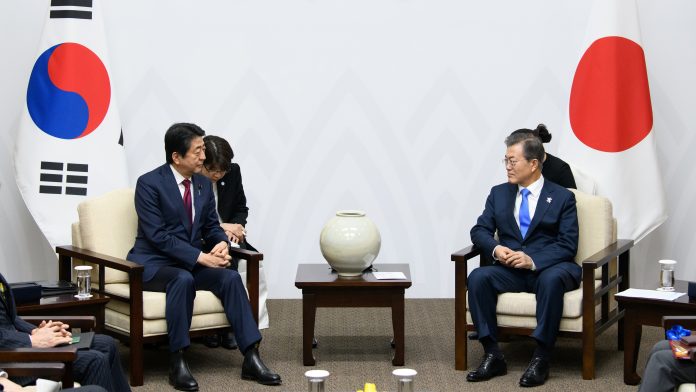

First, the three allies should reinvigorate the Trilateral Consultation and Oversight Group that was created during U.S. President Bill Clinton’s administration to coordinate policy and manage contingencies regarding North Korea. The three countries should also revitalize and expand defense cooperation. During the administration of former South Korean President Park Geun-hye, the three allies had begun to execute a regular program of trilateral military exercises. But the exercises ended five years ago, when disputes over World War II history returned to the forefront of Japanese-Korean relations under former South Korean President Moon Jae-in.

In addition to resuming missile warning and tracking exercises—in which the three navies practice data sharing on a simulated launch utilizing a common ballistic missile defense radar system— the three countries should conduct exercises and training in areas such as maritime surveillance, interdiction, and antisubmarine warfare. They should begin sending observers to bilateral exercises in Japan and South Korea and establish liaison offices with uniformed personnel at Republic of Korea-U.S. Combined Forces Command in Seoul and U.S. Forces Japan headquarters west of Tokyo to facilitate regular information exchange. And they should consider establishing a trilateral dialogue on strengthening extended deterrence in the region to supplement the bilateral dialogues that are underway.

Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington should also collaborate on economic issues, including efforts to shore up critical supply chains. The newly established U.S.-Japan Economic Policy Consultative Committee, chaired by the State and Commerce Departments with Japanese counterparts at the Foreign and Trade Ministries, could serve as a model. Each member has a great deal to offer on everything from global health to advanced technologies, such as semiconductors. The recent participation of Japan and South Korea in the U.S.-led Minerals Security Partnership was a useful step in this direction.

Finally, the three allies should engage in a high-level trilateral defense policy dialogue to increase transparency related to defense modernization. The annual defense ministers’ trilateral meeting at the Shangri-La Dialogue is important but should be supplemented by additional regular engagement at the deputy secretary or undersecretary level. As its plans take shape, Japan should use these venues to brief South Korea on its new national security strategy, which is planned for release in late 2022. South Korea, in turn, should share information about its “Kill Chain” program—Seoul’s strategy for detecting and preempting a North Korean attack—and its cruise and ballistic missile development.

Given China’s increased threats against Taiwan and the impact a conflict in the Taiwan Strait would likely have on Japanese and South Korean security, it is time for the three allies to engage in trilateral discussions regarding Taiwan contingencies. As an initial step, the three countries could consider a tabletop exercise to begin exploring coordinated responses in the event of a crisis in the Taiwan Strait.

DISTANT NEIGHBORS

Improving Japanese-South Korean relations will ultimately require dealing with political sensitivities related to history, including those stemming from Japan’s occupation of the Korean Peninsula before and during World War II. In particular, many South Koreans claim that Japan has not paid adequate recompense for its use of forced labor and the Japanese military’s exploitation of Korean women who were pressed into sexual servitude during the war.

The South Korean Supreme Court in 2018 ruled that several Japanese companies must compensate Korean workers who performed forced labor during the war; the disposition of this and other cases is still being considered in the South Korean court system. Japan asserts these cases are inconsistent with the 1965 peace treaty between the two countries, which states, “claims . . . between the Parties and their peoples . . . have been settled completely and finally.” Tokyo is pressing Yoon to get these cases dismissed.

READ ALSO: US: DARPA successfully tests hypersonic missile

The political sensitivities in both countries surrounding issues of history are real and should not be dismissed. Kishida will be under pressure from conservatives in his party, who will insist that the onus is on Yoon to repair frayed relations, given the widespread view in Tokyo that Moon, the former South Korean president, was responsible for rekindling the history disputes.

Although Yoon has come out strongly in favor of improving relations with Tokyo, his party’s lack of control over the legislature and Yoon’s lack of any early “wins” with Japan—such as Japanese action to restore South Korea to the “white list” of countries exempt from licensing requirements on sensitive technology exports—will restrict his ability to reach out to Tokyo. The resolution of issues related to history is likely to take time. And any solutions will not necessarily be fully satisfying to either side.

Nevertheless, a mutually satisfactory resolution of these issues should not be a condition for improved trilateral cooperation. Both efforts should proceed in parallel. The challenges all three countries face demand focusing on the future and moving forward. In the past, the three allies could absorb the strategic costs of weak trilateral ties and a weak Japanese-South Korean relationship. Those days are gone.