Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is pushing Europe toward a new era of unshackled fiscal spending as the region rushes to respond to an upturned geopolitical order.

A year when the European Union was set to reassess emergency budget largess stoked by the pandemic may be turning into another chapter in its tolerance of less restrained public finances and burgeoning debt. Money will now be needed for everything from enhanced military capabilities to alternative energy supplies.

The shift has been heralded by Germany’s decision to set aside 100 billion euros ($112 billion) for defense, a revolution in a country previously wedded to a timid military stance and a disdain for borrowing. That’s shining a path for a region where the need for security and stability increasingly is now likely to trump fiscal reticence.

More spending in Europe’s biggest economy and elsewhere suggests the prospect of a stimulus cushion to any growth threat from the war. Such a challenge posed by the conflict may also set the tone for new EU budgetary guidelines due this week.

“Germany can no longer stand up and act as fiscal disciplinarian while setting up one special fund after the other,” said Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg Bank in London. “European fiscal rules themselves won’t change, but the way they’re implemented will. Priorities have shifted.”

Against that backdrop, on Wednesday the European Commission will unveil budgetary guidance for 2023, intended to tackle ballooning national debt by reactivating curbs on spending suspended in 2020 for the pandemic.

Such ambitions may now be waning. Instead of strict limits, the commission wants to give governments qualitative recommendations, according to an EU official who declined to be identified citing the confidentiality of discussions. Growing uncertainty could force a suspension of rules for another year, which isn’t being considered now but could become an option after a reassessment in May, the official said.

That would buy time as countries debate the fiscal regime, known as the Stability and Growth Pact. One possible outcome could include the creation of an exception for climate-friendly spending, though nations such as France, Poland and Romania also want special treatment for defense.

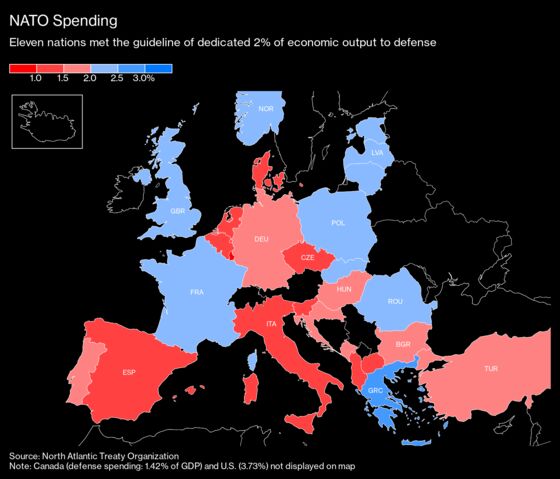

It’s not clear if Germany would support that, even though Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s shift in stance was emphatic. On Sunday he proposed to propel military spending above NATO’s target of 2% of output. That’s bold in a country whose World War II legacy has impeded the buildup of military might, and where voters cherish fiscal prudence.

“There seem to be two worlds now: the normal one in which saving money is still king, and the emergency one in which big spending is part of a forceful response,” said Philippa Sigl-Gloeckner, a former finance ministry official who leads Berlin think tank Dezernat Zukunft-Institute for Macrofinance. “It’ll take a long time for a normal world to return.”

Other countries are following suit. In the Netherlands — one of Europe’s so-called frugals preaching fiscal reticence — Defense Minister Kajsa Ollongren pledged on Monday to deliver a plan to boost spending to the NATO standard from about 1.4% currently.

“Many member states will reconsider military expenditure,” said Zsolt Darvas, a senior fellow at the Bruegel think tank in Brussels.

The current crisis has also seen regional action on defense. EU governments agreed to ship military supplies to Kyiv, while their European Peace Facility will buy 450 million euros of arms for Ukraine, a collective purchase that is the first of its kind.

Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi said on Tuesday he would prefer such spending at the EU level. One way to do that could be via its Recovery Fund established to rebuild economies after the pandemic.

“What’s clear to everyone is that we need to spend more on defense,” said Sebastian Dullien, director of Germany’s IMK Macroeconomic Policy Institute. “The EU has always liked to build on existing tools. Topping up NextGenEU to finance joint defense projects or upgrades to the energy network would make sense.”

Scholz’s move to speed construction of two liquefied natural gas terminals could augur further investment there and elsewhere, perhaps toward the so-called energy union craved by EU officials. Better physical integration would help: Spain has around one third of the bloc’s capacity to import LNG, but transit links to the rest of the continent are limited.

READA ALSO: Russia: Putin move makes West’s unity tightens overnight

Aside from defense and energy infrastructure, it’s feasible the conflict could incite other spending. Bank of Portugal Governor Mario Centeno, a former finance minister who used to lead meetings of his euro-zone colleagues, pointed this week to the possibility that governments may need to protect citizens from further inflation stoked by fuel costs.

“If needed, income-support mechanisms should be set up at the fiscal level to cope with those difficulties,” he said in an interview.

And into the future, there’s another fiscal cost the EU could face if somehow the conflict ends without Ukraine’s annexation by Russia. If its application on Monday to join the bloc were successful, a whole spending program might need to be devoted to rebuilding the country.

However the situation unfolds, the change in perspective heralded by Germany now looks increasingly permanent.

“With the invasion of Ukraine, we are in a new era,” Scholz told the Bundestag on Sunday. “This new reality requires a clear response. We have given it.”