Analysis: After the coup, Washington seems satisfied with a partial solution that restores aid and re-establishes Khartoum’s intern

Almost two months after Sudan’s military usurped control of the state, the anti-coup resistance remains strong.

Across Sudan, men and women have been taking to the streets, demanding the restoration of civilian control of the government to put the democratic transition back on track.

But the military’s grip seems to be increasingly entrenched, albeit challenged with each passing day. Clashes between security forces and protestors have resulted in the death of several dozen citizens.

Military and civilian leaders last month signed a political agreement that reinstated Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. He is to head a new technocratic cabinet until elections, planned for 19 months down the road.

However, for most Sudanese people this reinstatement merely gives a civilian face to a military coup and does nothing to reverse the events of 25 October. Ultimately, the agreement is about whitewashing the military’s power grab.

“Almost two months after Sudan’s military usurped control of the state, the anti-coup resistance remains strong”

It is no secret that the backsliding of Sudan’s democratic experiment does not concern certain states in the region. This is particularly true regarding counterrevolutionary regimes that feared how Sudanese democracy could inspire populations across the Middle East and Africa.

For states like Egypt, Israel, and some Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members, military-backed authoritarianism is far preferable to democracy in Sudan.

“Sudan constituted a threat of a good example of an Arab nation where the people had agency, they thought strategically, they employed strategic non-violent action effectively, and were able to bring down a long-entrenched autocratic regime and to make important pathways towards democratic self-governance,” said Dr Stephen Zunes, a professor of politics and international studies at the University of San Francisco, in October.

The project aimed at democratising Sudan following three decades of a brutal dictatorship was “obviously something [officials in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt] did not want to see succeed. They would find it very much in their interest to see it fail,” affirmed Dr Zunes.

“Whether they actually played a role in this [coup], I have no idea, but there is no question that [those regional powers] are pleased at these developments.”

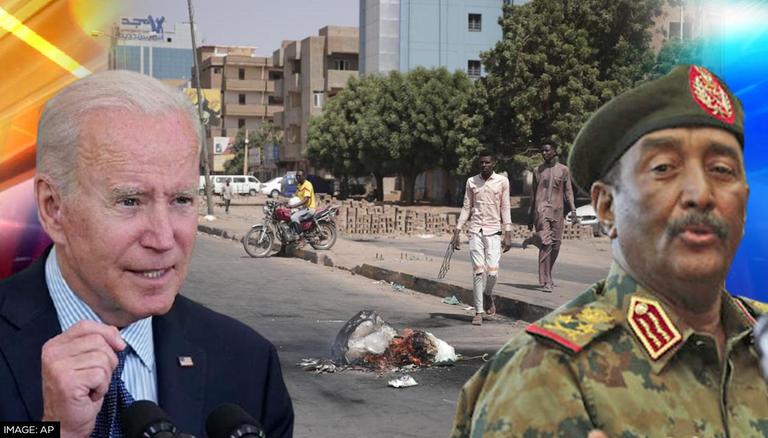

The Biden administration responded to the events of 25 October by firmly denouncing the incident and calling on the Sudanese military to respect civil liberties and restore civilian leadership.

Washington also put on hold $700 million of aid to try and pressure the generals in Khartoum into reversing the coup.

“US Envoy for the Horn of Africa [Jeffrey] Feltman worked tirelessly to head off the coup in October, spending several days in Khartoum just before the coup, and helped broker behind the scenes the partial deal returning civilian Prime Minister Hamdok to power, just as the Americans along with the British played an important role in 2019 to broker the initial deal for a transition to democracy,” explained Dr William Lawrence, a professor at American University, in an interview with The New Arab.

“But the US can do much more to support the Sudanese people in their quest for democracy and dignity.”

Thus far, the US has not imposed any sanctions on Sudan’s generals, nor has the administration officially called the overthrow a “coup,” just as the Obama administration never referred to any “coup” in Egypt in or after 2013.

At times, the US seems satisfied with a partial solution that restores critical socio-economic aid to Sudan and re-establishes its international relations but does not meet the demands of the Sudanese people for a faster civilian takeover of government.

Experts such as Cameron Hudson, a non-resident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center, believe that the West will probably not apply much pressure on the generals in the country. In general, the US and other Western governments seem to be attempting to pretend as though Sudan’s transition only temporarily veered off course.

As Hudson put it, there increasingly seems to be an intention on the part of Western states to “minimize its losses” and “preserve investments” in Sudan, which ultimately means accepting the coup with the minimal requirement that at least some civilian leaders will be in the regime.

At the end of the day, Biden’s team is acting cautiously while avoiding bold moves or any significant actions against Sudan’s rulers post-25 October, despite initially withholding most of the aid. The White House does not want to become heavily involved in Sudanese affairs, especially when they likely see the Ethiopian conflict as a higher priority.

In part, this might be an effort to avoid actions that could push Sudan closer to China and/or Russia’s orbits of influence. Within this context, the US administration has been trying to increasingly rely on two of its close Gulf partners – Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – to influence Sudan’s situation in ways that do not require heavy US involvement.

On 3 November 2021, the US Department of State released a highly unusual “Joint statement by the QUAD for Sudan, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the United States of America, and the United Kingdom, on the developments in Sudan.”

The media note stated that the four countries’ “call for the full and immediate restoration of its civilian-led transitional government and institutions”, the pursuit of “cooperation and unity in reaching this critical objective”, the release of those detained in relation to the military takeover, and the lifting of Sudan’s state of emergency.

The note also condemned the use of violence, encouraging “an effective dialogue between all parties” and for all parties to ensure that the peace and security for the people of Sudan is a top priority.”

“Washington is happy to farm out the handling of the Sudanese crisis to the Gulf’s most conservative regimes”

Rarely does Washington put out joint statements with the Saudis or Emiratis that call for civilian control of Arab countries or protection of democratic institutions. This public statement in support of the civilian government was even more surprising considering Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s history with some of the coup’s most influential leaders.

For years, both the Saudis and Emiratis have supported General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti. That relationship goes back to 2015 when both generals were part of Sudan’s deployment of 15,000 troops to support the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen.

In fact, Burhan had been in charge of coordinating the Sudanese military’s operations with the Saudi-led coalition and Hemedti had deployed as head of the Sudanese paramilitary force known as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). It is also important to note that of the Sudanese fighters in Libya, some were duped into going based on promised security jobs for them in the UAE, according to Dr Lawrence.

However, this support didn’t come to fruition until Sudan’s 2019 coup, when the UAE and Saudi Arabia threw their support behind both figures and the Transitional Military Council. Within ten days, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi had committed $3 billion in direct aid to the new regime, underscoring how these two Gulf powers quite successfully leveraged their financial resources and ties to the country’s security state to secure a strong hand of influence in post-Bashir Sudan.

Given their history with the Sudanese military, it is important to question the seriousness of this notion of Saudi Arabia and the UAE supporting Western efforts to restore civilian rule in Khartoum. Rather than working with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi to defend democracy in Sudan, it seems fair to wonder whether the White House is merely attempting to put regional Arab states in charge of the Sudan file regardless of how their interests in Khartoum may differ from those of Washington and London.

“The Biden administration turning to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the UAE for pressure on Sudan’s military leaders is in itself a nonsensical proposition, given the UAE’s well-entrenched preference for strict, top-down modes of governance,” Jalel Harchaoui, a researcher at Global Initiative, told TNA.

“The turn of phrase just means that Washington is happy to farm out the handling of the Sudanese crisis to the Gulf’s most conservative regimes.”

In the grand scheme of things, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s actions can be explained by them acting in their own self-interest. Officials in Saudi Arabia and the UAE are both attempting to leverage their networks and clout in Sudan, cultured from years of economic and diplomatic support, to stabilise regional security and gain the favour of the Biden administration.

While both Gulf countries would favour military rule, they recognise that a coup that installs leaders whom they have long supported may not necessarily be the best way to stabilise Sudan.

READ ALSO: Resistance: Palestinian Islamic Jihad, Hamas agree to step up attacks against Israel ‘s terror

Another open question is whether the two GCC states are shifting strategically or tactically. “We have seen tangible improvements in the Saudi and Emirati foreign policy positions whether in supporting the Libyan political process, rapprochements with Qatar and Turkey, and even tentative rapprochements with Iran and tacit support for nuclear negotiations,” said Dr Lawrence.

“They are increasing coordination with the Biden administration, and that in the context of considerable pressure from Congress in relations to the use of US weapons in Yemen,” he added. “What remains unclear is whether the two Gulf countries are reorienting their strategies or pragmatically hedging their bets.”

There are good reasons for everyone, including the GCC countries, to question whether Sudan existing under military rule will bode well for stability. On the contrary, with most Sudanese citizens believing that the generals lack the legitimacy to govern the country, even on an interim basis, an escalation of violence is a potential scenario to consider seriously.

Moreover, Gulf countries pursuing counterrevolutionary agendas in Sudan – along with other powers such as Russia, Israel, and Egypt – risk creating problems for their image among ordinary citizens should the military regime in Khartoum grow increasingly unpopular in the weeks and months ahead.